Measure Theory and Differentiation (Part 1)

21 Feb 2021 - Tags: measure-theory-and-differentiation , analysis-qual-prep

So I had an analysis exam yesterday last week a while ago

(this post took a bit of time to finish writing). It roughly covered the material in

chapter 3 of Folland’s “Real Analysis: Modern Techniques and Their Applications”.

I’m decently comfortable with the material, but a lot of it has always felt

kind of unmotivated. For example, why is the Lebesgue Differentiation Theorem

called that? It doesn’t look like a derivative… At least not at first glance.

A big part of my studying process is fitting together the various theorems into a coherent narrative. It doesn’t have to be linear (in fact, it typically isn’t!), but it should feel like the theorems share some purpose, and fit together neatly. I also struggle to care about theorems before I know what they do. This is part of why I care so much about examples – it’s nice to know what problems a given theorem solves.

After a fair amount of reading and thinking1, I think I’ve finally fit the puzzle pieces together in a way that works for me. Since I wrote it all down for myself as part of my studying, I figured I would post it here as well in case other people find it useful. Keep in mind this is probably obvious to anyone with an analytic mind, but it certainly wasn’t obvious to me!

Let’s get started!

To start, we need to remember how to relate functions and measures. Everything

we say here will be in

If

Moreover, given any regular borel measure

is increasing and right continuous.

This is more or less the content of the Carathéodory Extension Theorem.

It’s worth taking a second to think where we use the assumptions on

This is not a big deal, though. A monotone function is automatically continuous except at a countable set (see here for a proof) and at its countably many discontinuities, we can force right-continuity by defining

which agrees with

It turns out that Lebesgue-Stieltjes measures are extremely concrete, and

a lot of this post is going to talk about computing with them2. After all,

it’s entirely unclear which (if any!) techniques from a calculus class carry

over when we try to actually integrate against some

Given a positive, locally

Moreover, if

The locally

Something is missing from the above theorem, though.

We know sending

Lebesgue-Radon-Nikodym Theorem

Every measure

for some measure

Moreover, we can recover

for almost every

People often write

In the case

The converse needs a ~bonus condition~. In order to say

As an exercise, do you see why this condition is necessary? If

In the case of Lebesgue-Stieltjes measures, Lebesgue-Radon-Nikodym buys us

something almost magical. For almost every

Now we see why we might call this

In fact, we can push this even further! Let’s take a look at the Lebesgue Differentiation Theorem

For almost every

Why is this called the differentiation theorem?

Let’s look at

For

So this is giving us part of the fundamental theorem of calculus4! This theorem

(in the case of Lebesgue-Stieltjes measures) says exactly that (for almost every

Let’s take a moment to summarize the relationships we’ve seen. Then we’ll use these relationships to actually compute with Lebesgue-Stieltjes integrals.

Moreover:

-

By considering

-

By considering

-

Indeed,

-

And

Why should we care about these theorems? Well, Lebesgue-Stieltjes integrals

arise fairly regularly in the wild, and these theorems let us actually

compute them! It’s easy to integrate against

Then this buys us the (very memorable) formula:

and now we’re integrating against lebesgue measure, and all our years of calculus experience is applicable!

Of course, I’ve left out an important detail: Whatever happened to that

measure

Let’s write

Recall our interpretation of this function:

So

Indeed, we see that

So

It’s finally computation time! Since we know

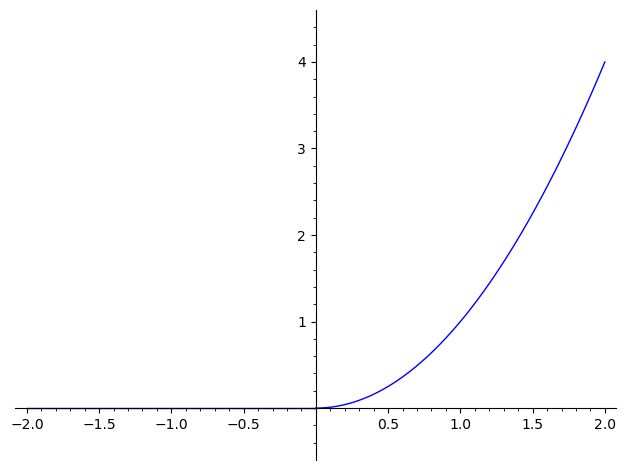

Let’s start with a continuous example. Say

So

Say we want to compute

We can compute

But both of these are integrals against lebesgue measure

That wasn’t so bad, right?

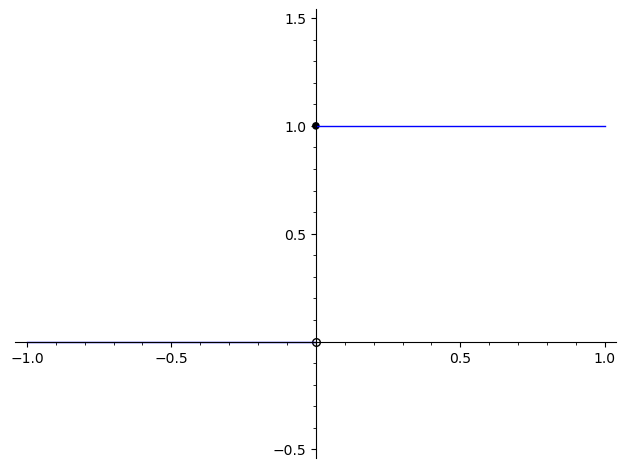

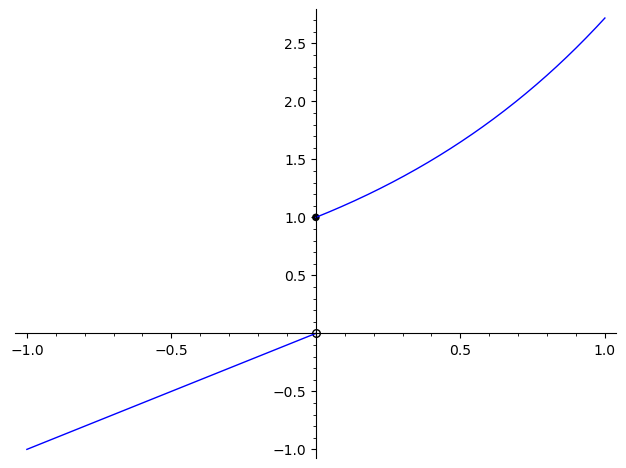

Let’s see another, slightly trickier one. Let’s look at

You should think through the intuition for what

In the previous example,

Let’s start with the places

We can also see the point

So to compute

we can handle the

We know how to handle dirac measures:

And we also know how to handle “classical” integrals:

So all together, we get

As an exercise, say

Can you intuitively see how

Can you compute

As another exercise, can you intuit how

What is

Ok, I hear you saying. There’s a really tight connection between

increasing (right-)continuous functions

But doesn’t this feel restrictive? There are lots of functions

Of course, to talk about more general functions

This post is getting pretty long, though, so we’ll talk about the signed case in a (much shorter, hopefully) part 2!

-

I was mainly reading Folland (Ch. 3), since it’s the book for the course. I’ve also been spending time with Terry Tao’s lecture notes on the subject (see here, and here), as well as this PDF from Eugenia Malinnikova’s measure theory course at Stanford. I read parts of Axler’s new book, and while I meant to read some of Royden too, I didn’t get around to it. ↩

-

As an aside, I really can’t recommend Carter and van Brunt’s “The Lebesgue-Stieltjes Integral: A Practical Introduction” enough. It spends a lot of time on concrete examples of computation, which is exactly what many measure theory courses are regrettably missing. Chapter 6 in particular is great for this, but the whole book is excellent. ↩

-

We can actually relax this from balls

-

There’s another way of viewing this theorem which is quite nice. I think I saw it on Terry Tao’s blog, but now that I’m looking for it I can’t find it… Regardless, once we put on our nullset goggles, we can no longer evaluate functions. After all, for any particular point of interest, I can change the value of my function there without changing its equivalence class modulo nullsets. However, even with our nullset goggles on, the integral

-

In no small part because I’m not sure how you would actually integrate against a singular continuous measure in the wild… ↩