Checking Concavity with Sage

09 Mar 2021 - Tags: sage

I haven’t been on MSE lately, because I’ve been fairly burned out from a few weeks of more work than I’d have liked. I’m actually still catching up, with a commutative algebra assignment that should have been done last week. I was (very kindly) given an extension, and I’ll be finishing it soon, though.

I meant to do it today, but I got my second covid vaccination earlier and it really took a lot out of me. I’m feverish and have a pretty bad migraine, so I didn’t want to work on “real things”, but I still wanted to feel productive… MSE it is.

Today someone asked a question, which again I’ll paraphrase here:

Why is

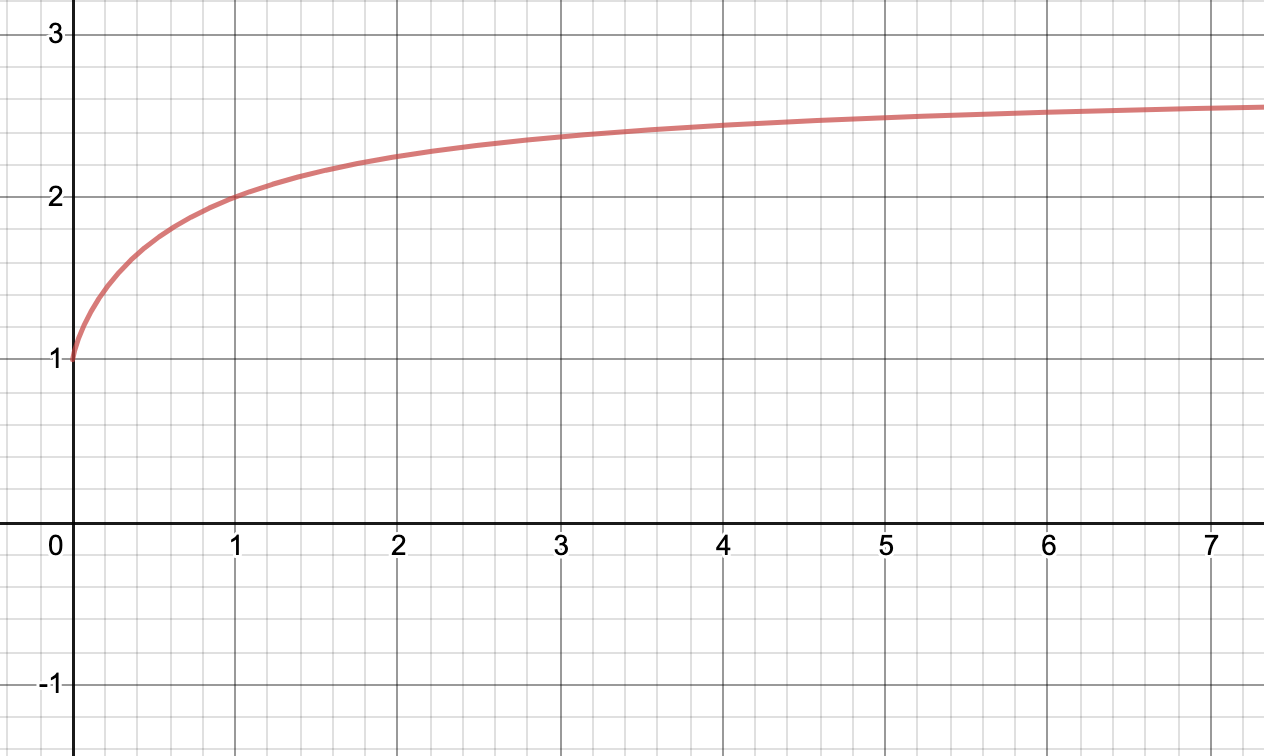

It clearly is concave. Here’s a picture of it:

Obviously it has an asymptote at

Thankfully, we can use sage to automate away most of the difficulties. I’ll more or less be rehashing my answer here. The idea is to put this example of using sage “in the wild” somewhere a bit easier to find than a stray mse post.

Showing that a function is convex (resp. concave) is routine but tedious,

especially when that function is twice differentiable. Then we can just check

We start by defining

xxxxxxxxxxf(x) = (1+1/x)^xsecondDerivative = diff(f,x,2)show(secondDerivative)In a perfect world, we could just… ask sage if this is

xxxxxxxxxxsolve(secondDerivative < 0, x)This gives a list of lists of domains, and if you intersect all the domains

in some fixed list, you get a region where the second derivative is

Let’s look at the second derivative again. We as humans can see how to clean it up a little, so let’s do that first:

Since

One obvious way we might try to simplify things is by turning our expression

into a rational function. After all, polynomials are more combinatorial

in nature than things like

So plugging in

But that means our expression of interest is upper bounded by

and we’ve reduced the problem to showing

and in the interest of offloading as much thinking as possible to sage, we see

xxxxxxxxxxassume(x > 0)bool(-1/(x^3 + 2*x^2 + x) < 0)and so

This was fairly painless, but we got pretty lucky with that estimate for

We’re at least a little bit out of luck, since Richardson’s Theorem shows that it’s undecidable whether certain (very nice!) functions are nonnegative. As an easy exercise, can you turn this into a proof that checking convexity is undecidable on some similarly nice class of functions?

Even though logicians came to ruin the fun (as we have a reputation for doing, unfortunately…), I’m curious if any kind of result is possible. Maybe there’s some hacky solution that works fairly well in practice? Approximating every nonpolynomial by the first, say, 50 terms of its taylor series comes to mind, but I’m currently struggling to get sage to expand and simplify expressions in way that makes me happy, so manipulating huge expressions like that is, at least for now, a bit beyond me2.

Again, all ideas are welcome ^_^

-

Another thing I tried was to get sage to do everything for us. But for some reason

bool(secondDerivative < 0)returns false, even when weassume(x > 0)… I suspect this is (again) because our expression is too complicated. After all, it seems like there are issues with much simpler expressions than this one. If anyone knows how to make this kind of direct query work, I would love to hear about it! ↩ -

Wow. I know I speak (and write) in run-on sentences, but this one’s on another level. I feel like I need a swear jar but for commas. ↩