Talk -- Let's Solve a Simple Analysis Problem. Together.

16 Feb 2022 - Tags: my-talks , featured , topos-theory

Last Friday I gave a talk in GSS where I tried to give a super concrete application of topos theory to “mainstream” mathematics. The idea was to solve a simple analysis problem, streamlining the argument by using the internal logic of a sheaf topos. The good news is that I think I was quite successful in making my point that “ordinary mathematicians” should care about topos theory and constructive logic. The bad news is that the last 10 minutes of my talk were false… It didn’t end up mattering, but I was still pretty torn up about it. Anyways, in this post I’ll give an overview of the talk, which should double as a nice description of how to actuallly use topos theory to solve problems. I’m planning to start a new series soon where I go over this proof in more detail, explaining the relevant aspects of topos theory along the way!

So then, what was the talk about?

Recall the Weierstrass Approximation Theorem, which says that

For every continuous

Let’s look into a natural generalization of this. Say

If we fix an

In case

has

In case

each of these are continuous, nowhere differentiable, and highly oscillatory.

With this in mind, a reasonable person might wonder if these

So, what to do? Notice that naively applying the theorem to each

This brings us to the, probably quite surprising, idea motivating the talk:

Let’s solve this analysis problem with high powered category theory and constructive logic!

I spent the next little while “defining” a topos as a category which

“looks like

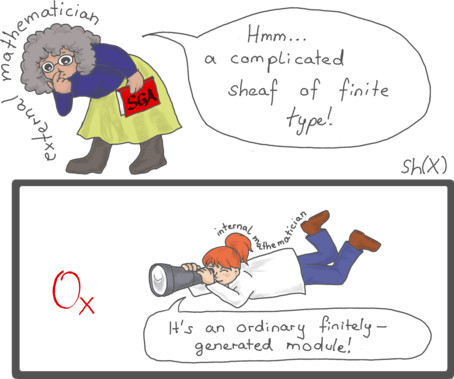

(Except when I drew this on the board, I used “weierstrass approximating polynomial” instead of “finitely generated module”)

Later in the talk I went into more detail about what exactly the “complicated external statement” is. But before we could go into that, we need to get an important caveat out of the way:

If we want to do mathematics inside of a topos, it has to be Constructive

What do I mean by “constructive”? Well to start, it shouldn’t use the axiom of choice. Indeed, even very weak principles like countable choice can fail3. It really doesn’t take too long (imo) to get used to working without choice4. But more importantly, we have to work without the Law of Excluded Middle (LEM), and this can take quite a bit of getting used to.

At this point in the talk I introduced the notion of a

sheaf on a topological space, as well as sheaf maps, and thus

the category

Then I said

that the truth values

At this point I talked about the natural numbers object in

Next I introduced the notation for forcing, where we say that

If we can prove

Here “theorem” is in scare quotes because I haven’t given anywhere near enough details to make this precise. But the purpose of the talk was to get the point across that we should care about constructive mathematics, and this idea of a theorem was good enough for that purpose.

Now that we have the soundness “theorem” in hand, let’s see if the weierstrass approximation theorem is even provable constructively! The next step of the talk was formally writing down the theorem we’re proving:

Thm (Weierstrass):

Now, it looks like there is a completely constructive proof of this theorem

(see chapter

In this proof we separate a sum into “good” and “bad” parts, which we approximate separately. But knowing that each summand is either “good” or “bad” requires LEM10.

At this point, I said that this proof does go through in

Normally I would use this as a learning experience, and show you all what my mistake was. But I was so muddled up I don’t think it would be worth it11.

Next up was forcing semantics. If we want to know how to externalize

theorems proved by mathematicians inside the topos, we need to know how to

interpret logic inside as statements we can see from outside. In the talk

I spent some time going over these, but they’re available in lots of places

already (for instance, on page

we unravel the outer universal quantifier, and find12:

For every

Unraveling this, we see:

For every

Then we see:

There is an open cover

That is, for every

That is,

Putting these pieces together, and choosing

There is an open cover

for every

which is exactly what we wanted!

Now, this is true because we have Bridges’ genuinely constructive proof of

the weierstrass approximation theorem. The proof that I gave in the talk,

involving LEM doesn’t quite provide this. Instead, it shows that

there’s a dense open set

I’m still thinking about the double negation modality, and a while ago I asked a question about this on mse.

I’m planning to start a series on topos theory and how we can actually solve problems with it, and this double negation stuff will definitely get its own post.

In the meantime, I’ll leave you with the abstract for the talk. Take care everyone, see you soon ^_^.

Solving An Easy Analysis Problem: Together.

*asmr voice* Let’s all take a break. Unwind. And solve a nice friendly problem in elementary analysis. Now that I’ve lulled you into a false sense of security, you should know that we’ll be solving this (very concrete!) problem by using heavy duty machinery from category theory and logic. In particular, we’ll be using the language of topos theory. In the process, we’ll see why people care about constructive mathematics, how category theory can solve real problems, and whether topos theory really is as scary as its reputation makes it out to be. We assume no background in topos theory, or indeed anything but basic category theory.

-

Don’t worry about the

-

As an aside, desmos shows this doesn’t happen, but it’s super nonobvious from just the definition of

-

In fact, this is probably the biggest reason I care about AC at all! ↩

-

Maybe this is because I did my undergrad in a very logic-heavy department, so lots of my classes were somewhat sensitive to choice anyways? ↩

-

I gave this definition without saying the word “functor” or “natural transformation” since I think it’s important for this talk to be accessible to people with as little category theoretic background as possible. ↩

-

Since truth values are opens, if the truth value associated to

So then

and we see that

I know I’m glossing over a lot of details here, but only because I want to write up a more detailed post in the nearish future. ↩

-

I elected to omit the fact that dedekind and cauchy reals are different in the absence of LEM or CC. ↩

-

As an aside, I was quite pleased with this section of the talk! I thought it flowed really well, since I gave this sheaf as my main example earlier, and then built up to it as the real numbers object. ↩

-

Candidly, though. I haven’t read the whole book. I looked through that chapter, but apparently Bridges uses some nonstandard definitions that might be misleading… I haven’t actually checked to see how this squares with the definitions we usually use in a topos. ↩

-

For a while I thought we could get around this since

For instance, let

So even comparing a real

-

If you really want to have an idea, I that that semantics in

Since

I’ll spend more time talking about double negation in a future post. ↩

-

using the fact that continuous maps