Why is the Completion of a Local Ring "More Local" than just Localizing?

04 Mar 2022

An oft-repeated piece of intuition I’ve seen while trying to learn algebraic geometry is that localizing a ring at a prime is like “zooming in” on that point. But if you want to zoom in “really close” then you have to take the completion of this ring… Why is that?

This is definitely an observation well known to experts

(and even many nonexperts, probably), but I know I would have liked to

have seen it spelled out explicitly, so here we are. I also would have

realized it sooner if I’d read Hartshorne sooner, since he gives this exact

observation in chapter

The idea, in hindsight, is obvious:

Open subsets in the Zariski topology are dense!

So knowing what happens in some neighborhood means knowing what happens almost everywhere!

Let

Then the ring of regular functions on

Now, what does it mean to “zoom in” on a point

Well, one obvious idea is to look at functions defined on smaller and smaller

open sets containing

but if

This sounds like a great definition of “local”, so what’s the problem?

Well, remember the boxed statement! Zariski open sets are dense,

and thus remember information from “most of”

Here is one striking example:

Let

Say the local rings of

This doesn’t sound too bad until you remember that

So even though we only knew that

Now, most of my geometric intuition comes from manifolds, and in that setting

this would be extremely strange! After all, manifolds are locally euclidean,

so if

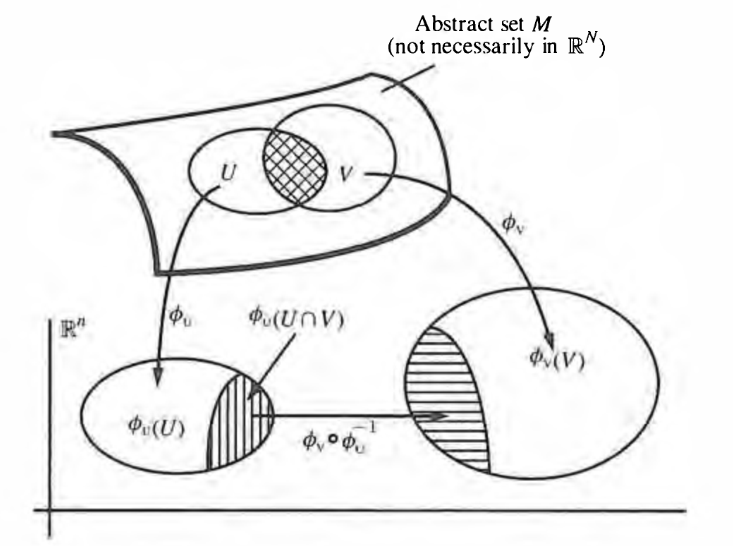

See, for instance, this picture I stole from the nlab2:

Every point on this surface has a neighborhood homeomorphic to an open disk,

and the same is true of every other point of every other

Intuitively, then we want to say that locally, every point of every variety “looks the same” as every other point, as long as the two varieties have the same dimension. We can’t get this behavior with just open sets in the case of varieties because there simply aren’t enough open sets to “get close enough” to a point.

But now let’s look at the completion.

The Cohen Structure Theorem says that any two complete regular local

rings containing the same field

So now if

This is the analogue in algebraic geometry of the fact that any two points of manifolds of the same dimension must have homeomorphic neighborhoods!

As a last aside, notice we had to squeeze in the word regular earlier. What does that mean?

Well manifolds have to be smooth everywhere, whereas varieties are allowed to have a small set of singular points. Broadly speaking, these are points where the tangent space has the wrong dimension. When a point isn’t singular, we call it regular, and the set of regular points is open and dense, so it’s most of the variety.

Since we expect the tangent space of a point to “look like” some small neighborhood of that point, it makes sense that “zooming in” too close to a singular point might make it look unlike the rest of the regular points on the variety, and indeed that’s the case.

At this point I encourage everyone to go look at example

I have some higher effort posts in the pipeline, but for now, it’s time for bed.

Stay warm, all! See you soon ^_^

-

I was scared of Hartshorne for a long time, and in hindsight I really didn’t need to be. I haven’t read it cover to cover, but I’m at a place now where chapter

I’ve actually had this post idea in my todo list for a little while now, and when I saw the exact observation spelled out in Hartshorne, it was the last push I needed to actually get to it. Of course that push was a few weeks ago now, but it takes time to actually get around to writing these posts, haha. ↩

-

This image actually has some ~bonus information~ about transition maps, which muddles the picture somewhat, but that’s what I get for using someone else’s diagram ↩