Externalizing Some Simple Topos Statements

13 Dec 2022 - Tags: featured , topos-theory

Hey all! It’s been a minute. I’ve been super busy with the UC strike and honestly I haven’t done math in any serious capacity for almost the past month. It’s been a lot of hard work trying to get fair contracts out of the UC, but I had a lot of travel plans this December to see my friends, so I’ve taken a step back from the picket line until January. Right now I’m in Chicago, so here’s an obligatory bean pic:

This means I have time to do math again, and it’s been really good for me to get back into it! I’ve started working with Peter Samuelson on some really cool work involving skein algebras, and I can’t wait to chat about it once I spend more time with it.

I also spent some time trying to understand manifolds in a topos of

So my last couple weeks, when I had the energy to do math after picketing, looked eerily like Julia Robinson’s famous description of her week:

I learned a ton while doing this, though, and I wanted to share some insights with everyone. It’s really hard to find examples of people taking statements in the internal logic of a topos and externalizing them to get “classical” statements, so I had to work out a bunch of small examples myself.

Let’s go over a few together, and hopefully make things easier for the next round of topos theorists looking to do this ^_^

Let’s start small. What does it mean to say that

Here, of course, we’re writing

So we’re saying that

First, let’s look at the case

We start with

Next we cash out our existential quantifiers for honest (generalized)

elements

Of course, in a topos of

So we end up with elements

But what does this mean? Well, in

Notice that the global elements of

Exercise: Show that the

Hint: Look at what happens to the identity element of the group

So then we have two ordinary functions

This brings us to an important observation about

Something is “locally” true in

So if we want a statement in

Can you find a formula

Great question! I’m glad you asked!

Say that instead of

Well again, we see that

and we cash out our existential quantifiers for local witnesses. That is,

there’s an open cover

Now (by yoneda), an element

This means

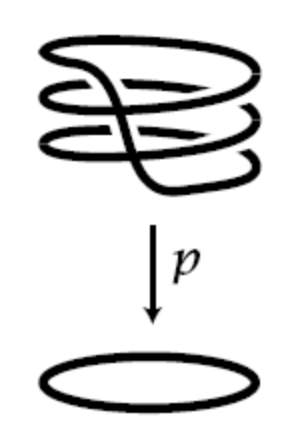

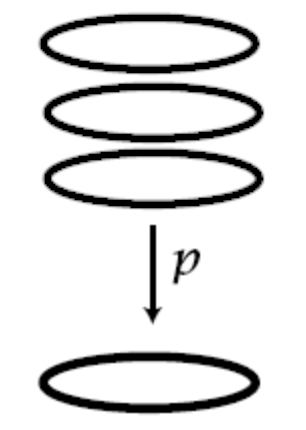

Notice that these local isomorphisms do not have to glue into a global

isomorphism! The simplest thing to do is to give a picture. If

then

despite the fact that they aren’t globally isomorphic!

From the perspective of the internal logic, the point is that the isomorphisms

over each

If you’ve never done it before, it’s worth going through this in detail!

Cover

Note, as an aside, that we’ve been working with an explicit choice of

finite cardinality:

This says that

Let’s start with the externalization. If

which we can cash out (again, see chapter VI in Mac Lane and Moerdijk) for

where

Now, just like existential quantifiers, disjunctions need only be true

locally. So in the case

Of course, this isn’t hard to do! Let’s take

If it’s not obvious, prove that

Then it’s easy to see that by taking

Next, let’s look at

Again, we’ll take an object

The flow of the computation is hopefully becoming familiar now.

For variety, since we’re working in a sheaf topos, let’s do this

computation with the sheaf semantics (Maclane and Moerdijk VI.7).

This lets us restrict attention to open subsets of

We start with

Now the universal quantifiers represent true statements for any local section.

That is, for each

Then since disjunctions need only be true locally, this is true exactly when

we can over

or

That is, on each

So an object

For a super concrete example, let’s look at

Here

Notice the truth values are open subsets of

But of course, this means that

Let’s give a bonus example as well, since this is a fairly subtle concept.

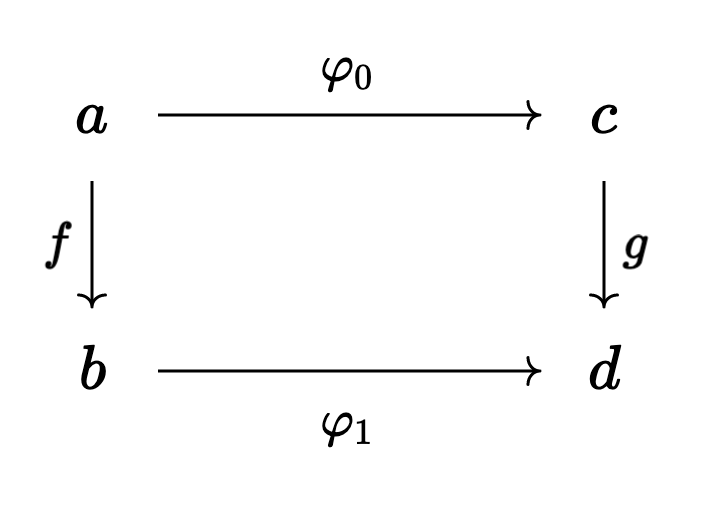

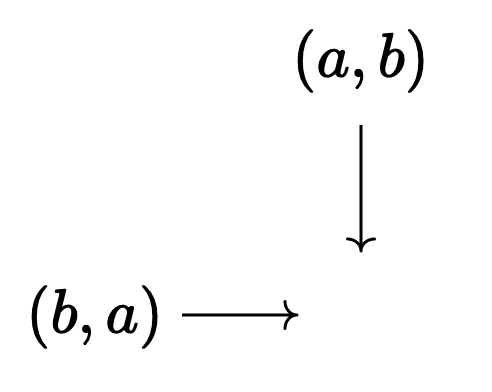

We’ll work in the arrow topos

I’ll leave much of this example as a fun exercise, since it’s important to get practice working these things out for yourself! If you want to check your work, though, I’ll leave brief solutions in a fold!

First, can you compute the object of truth values

solution

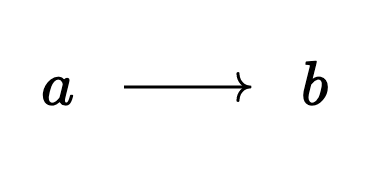

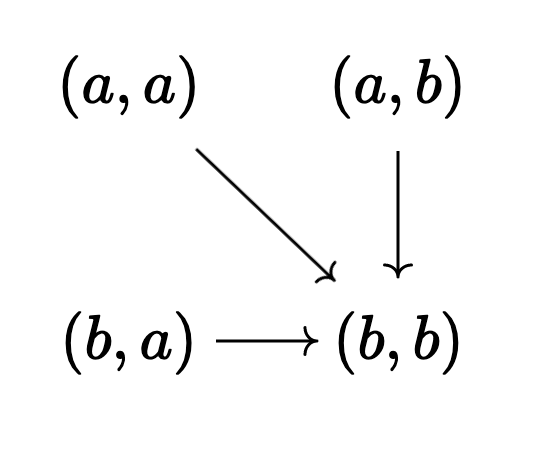

This is worked out in detail in chapter I of Mac Lane and Moerdijk (pages 35 and 36 of my edition) but briefly, we get

with

Remember that a subobject of

Then any

these correspond to the truth values

Next, can you figure out what it means for an object

solution

Let’s compute.

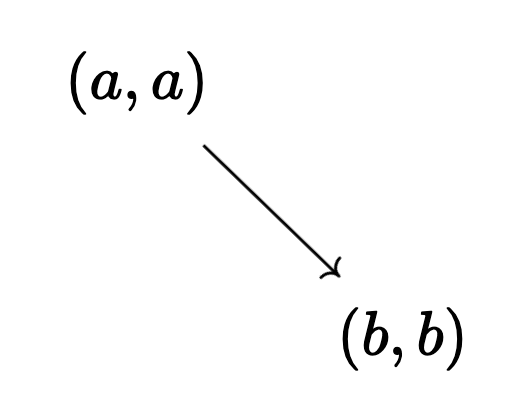

We quickly get to

Another, smaller, computation shows that

is a pair of surjections

With this in mind, when we unwind the disjunction to a pair of maps

it’s enough to look at the images of the maps

To have our best chance at covering

Unwinding

Then unwinding

Notice we have to restrict the domain to those elements who stay separated

after we apply

So if we want the union of

So the decidable objects of

Hopefully this also makes clear, in a more discrete way than the

This ring is not decidable since

This was a lot of fun, and hopefully you feel more comfortable externalizing

some simple statements after reading through these. It’s all about

practice practice practice, though, so I encourage everyone to come up with

their own easy examples and try externalizing them! I learned a ton while

writing this blog post, and that’s on top of everything I learned trying

to work out what a manifold inside

I won’t make promises, but I would love to write another post of this flavor sometime soon, where we can talk about something simple like linear algebra or basic analysis inside a topos. Of course, I have lots of ideas, and comparatively little time to write them all, so things will happen when they do ^_^.

Stay warm and stay safe, all! We’ll talk soon 💖

-

In particular, we’re planning to think about

-

Something like this is probably true for more general etendues, which (up to a cover) look like

-

Try

-

Also note that the existential quantifier really impacts things. Essentially we asked for

-

Briefly, a property is called decidable if a computer can check if the answer is yes or no.

A property is called semidecidable if a computer can check if the answer is “yes”, but we don’t know how long it’ll take. What’s worse, the code is allowed to loop forever if the answer is “no”! So really we get a “yes” or “maybe”.

Dually, we say a property is co-semidecidable if a computer can answer “no” or “maybe”. If you run it long enough and the answer is “no”, it will always say so. But if the answer is “yes” the code might loop forever.

As a (fairly easy?) exercise, show that something is decidable if and only if it’s both semidecidable and co-semidecidable.

To finish the brief explanation, equality is such an important predicate that we say

-

This should make intuitive sense. A topos of

Yet another way to see this (which I’m 80% sure is true) is by working in the slice topos. I’m pretty sure that

is the same thing as asking for

to name

Here the truth values are subobjects of

and

of course, since the complement of the diagonal is a sub-

Note this is not the case for

If we work with the monoid

(plus a self loop at

Then the product

(again, with a secret self loop at

The diagonal, of course, is a sub-

But now the off-diagonal is not a sub-

So the complement

In particular,

It also thinks it’s not false, for what that’s worth.

As a nice (slightly more challenging) exercise, figure out what the truth value of that statement actually is!

It’s still not fully clear to me what truth values in

Presumably in

If someone wants to work this out, I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments! This footnote is already getting super long, though, and I have the rest of the post to work on! ↩

-

This is obviously an extremely strict condition! If we think about the sheaf of real-valued continuous functions on

-

This is worth some meditation. There’s something model-theoretic happening here, where truth is preserved as we move from the domain to the codomain. But falsity does not need to be preserved (said another way, truth does not need to be reflected from the codomain to the domain).

So true things stay true, but false things can become true later on.

It’s possible for

Somehow the logic of the topos handles all of this for us, which doesn’t seem so impressive when we only have one arrow, but you can imagine as we increase the complexity of the category

Regardless, it’s not lost on me that

-

taken from Johnstone’s Rings, Fields, and Spectra, which should really be required reading for anyone interested in applications of topos theory! ↩