Chain Homotopies Geometrically

24 Jun 2022

The definition of a Chain Homotopy has always felt a bit weird to me. Like I know that it works, but nobody made it clear to me why it worked. Well, the other night I was rereading part of Aluffi’s excellent Algebra: Chapter 0, and I found a picture that totally changed my life! In this post, we’ll talk about two ways of looking at chain homotopies that make them feel more like their topological namesake.

(As an aside, I was reading through Aluffi because I’ve been thinking a

lot about derived categories lately, and I wanted to see how he motivated

them in an introductory algebra book. I’ll be coming out with a blog post1,

hopefully quite soon, where I talk about model categories and their close

friends

I want this to be a genuinely quick post, so I’ll be assuming some familiarity with algebraic topology, mainly homology and chain complexes. As a quick refresher, though:

A Chain Complex of abelian groups is a sequence

so that

We’ll refer to the entire complex by

In this notation, the chain condition is that

These first arose in topology. For instance, in order to study the (singular)

homology of a topological space

where

Then the Homology Groups of

I won’t says any more about this here, but if you’re interested you should read my old post on cohomology3. What matters is that this “boundary operator” literally comes from the boundary of a geometric object!

I also won’t try to motivate chain complexes in this post4. It turns out they’re extremely useful algebraic gadgets, and show up naturally in every branch of modern geometry, as well as in “pure” algebra such as group theory, module theory, representation theory, etc. Chain complexes are ubiquitious in math nowadays, and if you haven’t met them yet, you’ll surely meet them soon!

Motivation aside, what matters is that this construction is

functorial, and so a map

Moreover, it’s not hard to check that this

Next, topologically we have a notion of “homotopy”:

We say that two maps

We think of

For geometric reasons, we expect that two homotopic maps

Enter the chain homotopy!

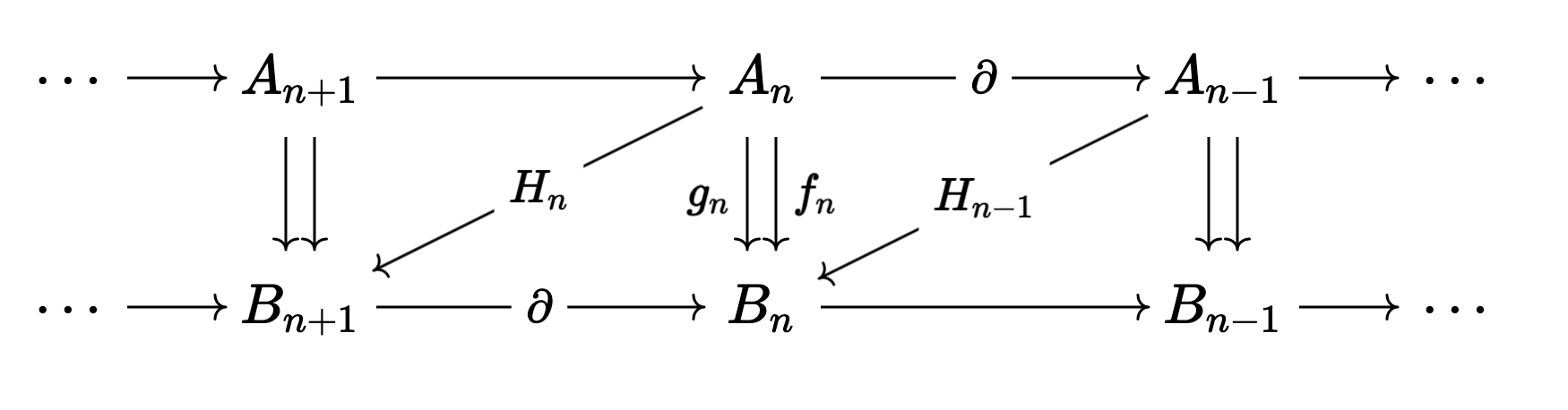

At this point I’m legally required to show the following diagram:

Now it’s a theorem that two chain homotopic maps induce the same maps

on homology. It’s then pretty easy to show that if

So this all works… but this condition has always seemed a bit odd to me. Where is this definition of chain homotopy coming from? It must be some translation from the topological notion of homotopy into the algebraic world… But how?

Let’s find out!

The first approach is the one that inspired me to write this post. You

can read the original on page

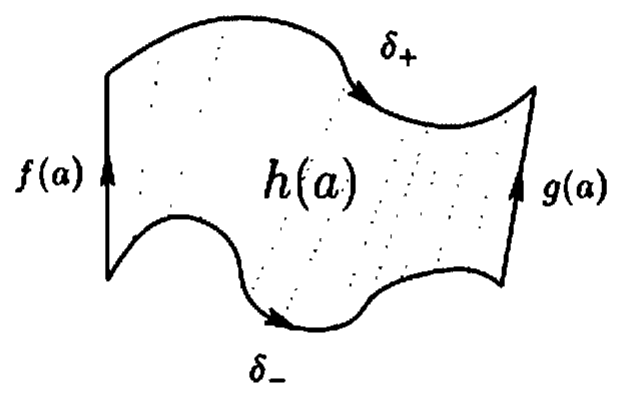

As an homage, let’s steal Aluffi’s diagram:

Let

Then

Now for the magic! Let’s look at the boundary of

But what is

So then

or

which we recognize as the definition of a chain homotopy!

There’s another, more conceptual, way to relate the notion of a chain homotopy to the classical topological notion of a homotopy. This time, we’ll go through the machinery of a model category.

Now, if I didn’t want to motivate homology in this post, I certainly don’t want to motivate model categories! Or even define them for that matter. I fully expect this material to be less approachable than what came before, but that’s not so big a deal8. To quote Eisenbud:

You should think of [this] as something to return to when more of the pieces in the vast puzzle of mathematics have fallen into place for you.

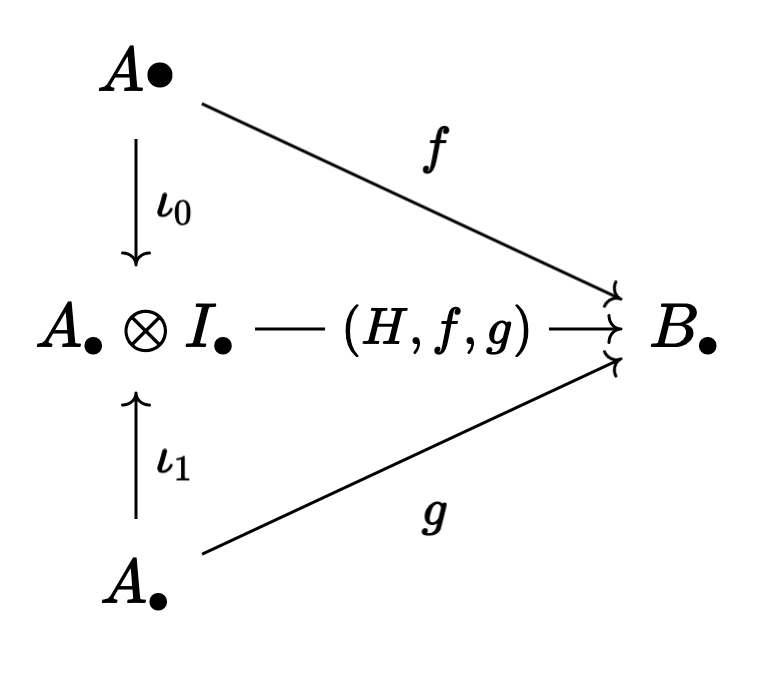

Now, remember what a homotopy was in topology. If

Is there a way to directly imitate this definition in the category of chain complexes? Surprisingly, the answer is yes!

What about the interval

How do we do it? Well, let’s build the (simplicial) chain complex of the interval!

We have two

So we can think of this chain complex

(with

Now, if we have two maps

Now here’s a fun (only slightly tricky) exercise11:

makes the following diagram commute

Honestly, it’s a good enough exercise to just construct

If you get stuck, you can find a proof in proposition 3.2 here

I’ve been working with chain homotopies for years now, and out of familiarity I’d stopped wondering what the definition really meant. Pragmatically this was probably good for me, but I remember in my first algebraic topology class being horribly confused by the origins of this definition, and I’m glad that I finally figured out how this definition relates to the underlying geometry! Hopefully you found this helpful too if you’re still early in your time learning about chain homotopies. To me, this makes the definition feel much more natural.

Now, though, it’s time for bed. Take care, all, and I’ll see you soon ^_^

-

Really a trilogy of blog posts… There’s a reason it’s taking so long. ↩

-

Believe me, I sympathize if you’re new to the subject. It gets worse, we often use

Thankfully, with experience you get used to this, and in the short term there’s always a unique way to assign any fixed

-

Wow… I sure did say I would write a sequal to this post… Over a year ago…

I’ll get to it one day, haha. ↩

-

After working on the model category and

-

If

For this reason, if

-

Again, apologies to those new to the subject. More precisely, for each

notice, as promised in an earlier footnote, we’re using

-

Astute readers will notice that a square is not a simplex, so we can’t really be reasoning about it using homology.

But anyone who’s made a grilled cheese knows we can divide a square into two triangles by cutting along a diagonal. Since

The fact that we can always cut up

It’s also worth noting that some people sidestep this issue by basing homology on “cubical chains” in

While this idea has gained a lot of traction in the HoTT community (since cubical foundations allow univalence to compute), it’s still somewhat nonstandard in the context of broader algebraic topology. See here for some discussion. ↩

-

You also shouldn’t have to wait too long if you really want to see me motivate model categories. Like I said at the start of the post, I’m super close to finishing a trilogy of blog posts, the first of which is about model categories!

If I remember (or when someone reminds me) I’ll link it here once the post is up. ↩

-

Obviously if we’re working with chains of

Also, I feel like there should be an “algorithmic” way of finding an interval object inside a model cateogry (again, really an

I want this to be a quick post, so I don’t want to look into it too much right now, but I would love to know if, say, every combinatorial model category has an interval object, and if we can reconstruct it (agian, maybe in the

If someone happens to know, I would love to hear about it ^_^ ↩

-

We can see that tensor products are the right notion of product (rather than the direct product) in a few ways:

First, the direct product would leave most of our chain complex unchanged. Contrast this with the tensor product, which successfuly gives us “off by one” pairs in each dimension that we expect (since we know we’re eventually going to recover the notion of chain homotopy)

Second, if you remember the Künneth Theorem, then you’ll remember that

Third, it seems like there’s a more general approach here that I don’t really understand. But again, I want this to be a quick post, so I won’t be doing that research myself (at least not tonight :P).

It looks like it has something to do with the tensor-hom adjunction, since

Then we should be interested in some kind of monoidal closed type structure on the category of chains, where we use

It seems like someone has made this precise (see remark 2.4 here, for instance), but I haven’t found any references myself. ↩

-

My instinct is to prove this, but I’m well over my planned one hour time limit on writing this post, and I have to wake up early tomorrow, so I should really get to bed.

So instead I’m taking the cop out as old as math itself, and I’m leaving this as an exercise.

I don’t feel too bad, though, since this is in the section that I said upfront would be a bit more technical, and the proof really isn’t hard (it’s a matter of unpcaking definitions more than anything else). Plus there’s a full proof on the nlab that I link to at the bottom of the exercise. ↩